|

| John Cale, Toronto, Jan. 1987 |

SHOOTING JOHN CALE WAS A VERY BIG DEAL. I knew it when I packed my camera bag and walked the handful of city blocks from my apartment to the club where he was performing, so you'd think I'd have shot more than a handful of frames on a single roll of 120 film when the man was actually in front of me. That I didn't says a lot about the very tight economy that I had to work under in the first few years of my career.

Cale was, after all, one of the original members of the Velvet Underground, and even during a relatively fallow period in his career in the '80s, his reputation was still considerable. I was grateful that I didn't have to interview him as well - that task fell to my friend Tim,

Nerve magazine's resident magus and far more knowledgeable about Cale's career since the Velvets.

I'm sure that he was just as intimidated as I was, since - thanks to his infamous and intense cocaine-and-brandy-fueled performances in the '70s - Cale had a reputation for being a difficult interview and portrait subject. I certainly couldn't think of a lot of photos I'd seen of him where he radiated anything like warmth.

|

| Mamiya C330 (not mine) |

I photographed John Cale not long after I'd bought my Mamiya C330, the first medium format camera I owned, and a serious step towards admitting that I wanted to do this professionally, since - as far as conventional wisdom had it - real photographers did at least some, of not all, of their work on a format bigger than 35mm. The John Cale shoot is the ninth sheet of negatives in my first binder of 120 film, just after my John Waters shoot.

The C330 is long gone - traded up for a pair of Rolleis and a Bronica SQa a couple of years after I bought it, when the numerous technical faults with the Mamiya's parallax lens system and very inelegant controls became too hard to handle. Unlike the cursed Nikon F3, though, I have very fond memories of the camera, and the very steep learning curve it took me on, most of it encompassing the year 1987. To that end, my posts for the next few weeks will concentrate on that year and the work I did with the camera.

|

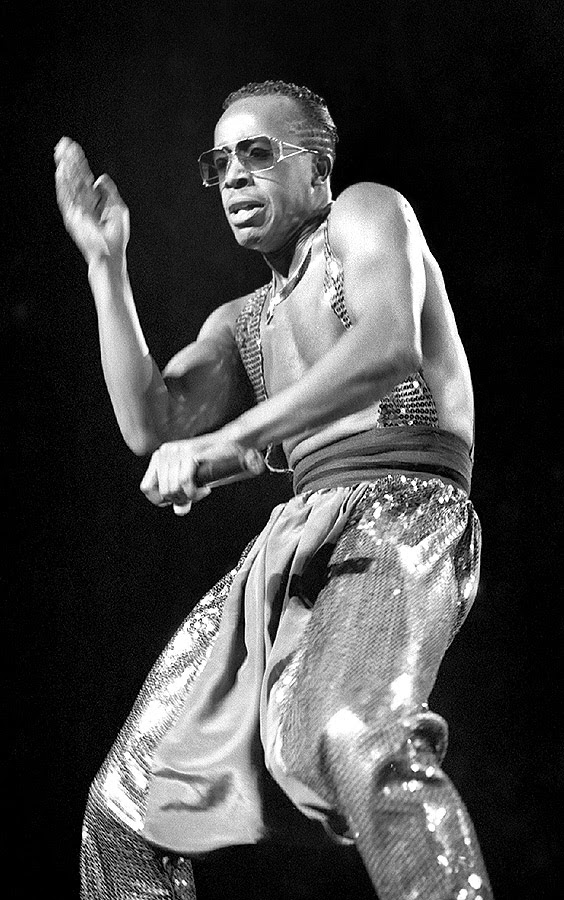

| Chris Spedding, Toronto, Jan. 1987 |

Cale was backed up on his gig at the Diamond Club by Chris Spedding, the session guitarist who'd played with everyone from Jack Bruce, Harry Nilsson and Roy Harper to Roxy Music, the Sex Pistols and Robert Gordon. He was a regular visitor to Toronto, and while I could have tried to get a portrait of him any number of times, I took the opportunity of having Spedding in the same room as Cale to snap a few frames from my single roll of black and white 120 with him.

My method was, at that point, a very hungry and poor one; I'd cradle the C330 with my right hand while holding a Vivitar flash with my left, tethered to the camera with a short cable. What I got was a hard, directional light that spilled into the background, thanks to the 105mm lens that required me to stand further away from the subject than a conventional 80mm would have placed me.

After focusing and composing the photo, I'd correct for the parallax by shifting the camera so the top of the frame lined up with the helpful little correction bar that moved up and down in the focusing window. Carefully aiming the flash, I'd trip the shutter with my thumb, making sure I didn't accidentally touch the shutter and aperture adjustment levers at the same time and overexpose the frame. I was light stand, tripod and photographer, all in one.

Quite by accident, this crude lighting scheme produced something vaguely like the Hollywood glamour portraits I'd loved for years, enhanced a little bit on the Cale/Spedding shoot by the bit of palm frond and curtain in the background of the shot, taken in the empty restaurant at the front of the Diamond. It ran big when Tim's piece was published in

Nerve, which was always gratifying.

Thanks to cradling the camera close to my chest while I worked, I ended up shooting Cale from below, accentuating the circumspect look he gave me for most of the shoot. I ended up printing a much cooler expression for

Nerve, but years later I've chosen a slightly less forbidding frame to scan, perhaps because the intervening decades have given me a chance to appreciate Cale's work, which is in significant stretches fare less austere and forbidding than his appraising glare.

|

| John Cale, The Diamond, Toronto, Jan. 1987 |

The shoot over, I walked home and swapped out my portrait gear for my

Spotmatic and headed back to the Diamond to shoot the show. Two years on either side of an album to promote, Cale was also newly teetotal and far from the chicken-butchering, hockey mask-wearing maniac of a decade previous. Still, it was an intense show. I'm sure he played "Fear," and I'm fairly certain that he did his trademark cover of "Heartbreak Hotel."

My live shots didn't have much to recommend them, however, probably because I doubtless felt I'd gotten what I wanted with my portraits, and this single frame is the only one worth scanning.

(UPDATE August 2018: I've gone back and re-scanned these portraits since, reasonably, I can do a much better job with them now, over three years later.)